Patients and doctors need to be on the same side.

I keep saying this, probably quite pointlessly, but it’s true; we are not each others’ enemy. If we become so, not only are we making the NHS a battleground, a horrible place for patients, and an unhappy place to work, but also an unsustainable organisation.

The last few days have seen lots of tweets and blogs about the Resilient GP website. The group have published a survey of their members on what they regard as unreasonable demands made by patients on GPs.

It’s not scientific, and it looks pretty unpleasant to me – doctors dissing what they see as unreasonable/silly demands. I think it’s far more nuanced.

For example

“Is there a pill so I can have a baby boy?” might be the request from a woman living in a society which does not value girls and where she may be under pressure to have an abortion if she carries a female child.

‘6 week pregnant woman attended out of hours because she felt her tummy was ‘too flat’ might represent a tormented fear that there has been a silent miscarriage, etc, etc.

My concern is that this posting will do more harm than good. Patients could recognise themselves, or think they recognise themselves. People who use the NHS unfairly are unlikely to pay any attention to this posting. People who need the NHS but already feel guilty and stressed about doing may read this posting and feel even worse about their own needs.

I also suspect that the posting reflects frustration with the way we are currently working, and the workload in primary care which is unsustainable.

The question of how we got here, and how we get out of it, is far more complex but also far more worthwhile.

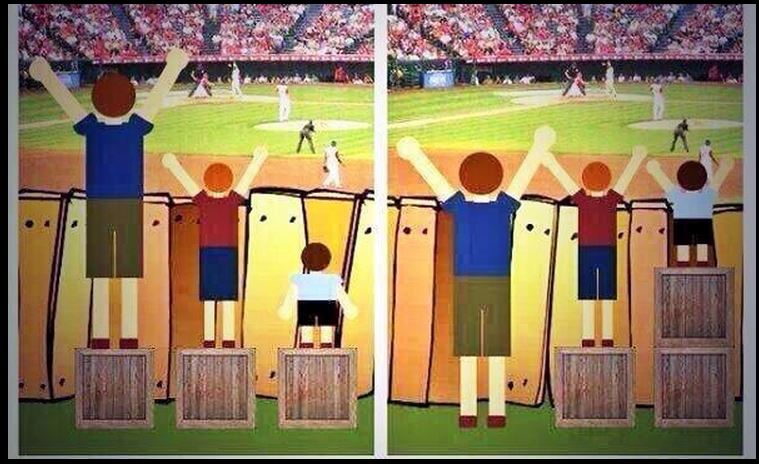

I think we should talk about fair use. I’m inspired by this depiction of equal vs fair (if anyone knows who has copyright please say so I can acknowledge)

The NHS is a limited system – doctors and nurses can’t clone themselves when it’s busy. Demand on GP has increased along with complexity and contract workload. People who have needs have to come before people who have wants. Everyone who uses the NHS should understand this. And every day this is enacted by citizens who wait behind someone more seriously ill in A+E, or who don’t ask for an emergency appointment in their GP surgery today because they are confident that their condition can wait a week to be seen instead. We rely on citizens being sensible about sorting their own priority level and whether they have a want that is a reasonable NHS use. But there are problems with this system.

Clearly there is unfair use of the NHS. For example, there are a small group of people who make clearly unjustified demands/ complaints and/or are rude or abusive towards NHS staff. Personally I think the NHS is not always supportive enough towards its staff and should investigate and throw out complaints early when they are clearly silly, malicious or unjustified. (I should also say that there should be far faster and easier investigation of justified complaints, within a just culture, where we seek to understand problems and get things better rather than apportion blame, see here and here). For many people , however, their perceived want or demand is shaped by their circumstances – little social support, economic or social stress, poor literacy, difficult childhood, or other inter current health issues (especially mental illness.) And it’s also clear to me that there are other patients who have needs and don’t see their doctor because they feel guilty about doing so, they don’t want to bother the doctor, and they simply try and make do with how they are – in many ways, that’s ‘unfair’ too.

So when Resilient GP uses examples of, for example, a patient with a sore throat that cleared up before the appointment, but complained about the length of time to get an appointment, I think we should ask where the perceived need for a consultation comes from.

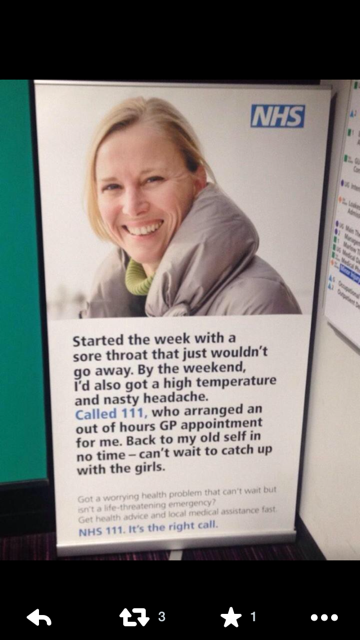

This was a poster from London at the end of last year. People are encouraged to phone 111 for a set of symptoms that sound suspiciously viral – and the kind of symptoms which need time to settle, and I don’t usually have anything to offer but reassurance, or that couldn’t be purchased at a pharmacy. There is nothing here about what symptoms are usually self limiting, what to do about that, what ‘red flags’ to look out for, and what doctors can offer beyond self-care. In other words, it’s an advert for a service, but not how to manage your health. It doesn’t give knowledge about what symptoms need attention from a professional, and what can be reasonably managed alone. It raises expectations of what medicine can do – and I would argue that it does so well beyond reality. Or take this

Again, I’m not even sure this is evidence based – a minor illness is exactly that. The question is: do major illnesses begin with minor illness symptoms and does earlier recognition mean that serious consequences can be avoided? I can’t find much in the way of literature to support the NHS thesis, and I’m concerned that medicalising ‘normal’ minor illness by suggesting that pharmacists should see this group of patients may be harmful. Most minor illnesses need time to settle, and things like cough bottles don’ t have good evidence behind them. It creates the idea that there is something which will ‘work’ and needs professional intervention. And if that intervention fails, is ‘something else’ needed instead? This is likely to create waste as well as misconceptions.

It would be far more useful for the NHS to give people information about what minor illnesses are, and when people should see a professional, and what to expect from illness. People are being told what to do – and not being given the opportunity to understand illness, or given the tools to self manage. We should not blame patients for not knowing as much as doctors do. We should not blame patients for being anxious or concerned about what we regard as minor symptoms (and that’s always easier in retrospect) especially when that anxiety is being driven by massive, non evidence based campaigns from the NHS/government.

Then there is the issue of what fair use of the NHS and ensuring that ‘fairness’ is distributed equally. This means that doctors should feel that they can challenge repeated unfair use – for example, if people are asking for things on prescription which are purchasable over the counter, minor illness schemes can help (the pharmacist deals with this at the counter). It should be OK for GPs to tell people about this and ask them to use this in future, meaning that there is more time for people whose problems need to be discussed with the doctor.

Promoting ‘fair use’ also means challenging the endless list of people who think that GPs can fix their problem; for example schools demanding a sick note for children off school due to illness (this is the school that needs challenged, not the parents), advise older people on staying married (an MP who made that comment) or NICE, who have decided that GPs should check that all their patients homes are warm every year (despite no trial evidence that this is useful) and that GPs should offer statins to people at a 10 % risk of a cardiovascular event every year, despite expert opinion saying that it would create an undo-able workload. The ongoing problem with GP access is in part related to this, but also related to policy being written by government for people like themselves – continually emphasising access beyond continuity, suiting people with few ongoing health needs the most. Have we challenged this enough? I don’t think so. And then there is the press release problem – academics whose answer to almost everything is that ‘GPs need to be more aware’ of whatever problem they identify. We need to get real: GPs are generalists, under huge pressure from multiple directions, and we need support and resources, and an understanding of how we work and what would help – and not endless vilification.

In other words, blaming patients is short sighted, unhelpful, and harmful, and creates divisions where we should be identifying the real problems and helping each other to better ways forward. I hope that Jeremy Taylor of National Voices, and others, can think about getting a meeting together where we can identify shared priorities and help each other to get, sustainably, to where we want to be.

3 Responses to “Fair use – don’t blame patients”